Author Archive

Protagonist

Protagonist is one of those films that utterly defies description; yet is absolutely stunning, moving, and fascinating in so many unexpected ways.

Actually it’s quite easy to describe: the hard part is having your description do justice to the film without the description seeming a bit goofy. The IMDB description is as good as any: “Protagonist explores the relationship between human life and Euripidean dramatic structure by weaving together the stories of four men: German terrorist, a bank robber, an “ex-gay” evangelist, and a martial arts student.” Oh and there’s puppets. Ancient Greek puppets.

But what a seriously masterful documentary by Oscar-winning director Jessica Yu.

Each of the four men, including former German terrorist Hans-Joachim Klein, tell their life stories, and ultimately how they challenged the fate that life seems to have presented them. Interspersed with their stories are puppets presenting Euripidean plays and elements highlighting the eternal struggle to control our own destiny. In effect, the director Yu has made these four men Greek tragic heroes.

The entire conceit works exceptional well; helped immeasurably by sharp editing, excellent “casting,” and remarkably good puppetry.

Students of the Baader-Meinhof era will be especially mesmerized by the segments featuring Hans-Joachim Klein. Klein’s life certainly plays out like a greek tragedy: a Jewish mother who was interned at Ravensbruck druing the war; only to commit suicide two years after the war and four short months after giving birth to Hans-Joachim. A stern police officer father who loved Hitler, and later became a law-and-order cop, hated the student protests of the 1960s. Hans-Joachim was a fairly uneducated member of the working class who found a life among the radicalized students of the late sixties. His rough and tumble background made him an ideal enforcer for the radical groups he supported, and eventually he became a member of the terrorist group the Revolutionary Cells. Klein participated with Carlos the Jackal in the horrendous 1975 raid on an OPEC minister’s meeting, getting shot in the process. Later Klein was recruited to participate in a forthcoming hijacking of an Israeli passenger jet to Uganda. Realizing the true anti-Semitic nature of the mission–and mindful of his own Jewish heritage–Klein begged off the mission and renounced terrorism.

There is not an ounce of guile in Klein’s interviews. He is contrite and regretful of his time as a terrorist, and incredibly self-aware of where and how things went wrong.

I have heard many former terrorists renounce their past; yet Klein is the only one who seems utterly shattered by it and incapable of rationalizing any of his actions.

The director, Jessica Yu, has made another documentary that is–if possible–even harder to describe. Yet In the Realms of the Unreal is equally wonderful. Movies like these are what Netflix was made for!

Listen to an interview I conducted with Jessica Yu.

And watch this short clip from the film, where Klein explains how the radical movement embraced him:

[flowplayer src=http://www.baader-meinhof.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Protaganist-Klein2.f4v splash=http://www.baader-meinhof.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/joachimsplash1.jpg]

The Baader-Meinhof Gang – History International [Registered]

1998 – Produced by ITN Factual for History International.

“The Baader-Meinhof Gang” is a one hour special created for History Channel International in 2007 as part of their “International Profile” series. The film benefits immensely for interview with former Baader-Meinhof Gang member Astrid Proll, family members of former terrorists, baader-meinhof.com site creator Richard Huffman (me!), and especially Baader-Meinhof biographer Stefan Aust. Clearly the producers had a very limited budget for acquiring footage, but this is balanced by the outstanding and accurate interviews.

Being part of the process of making this show, I was especially impressed at the care the producers and director took to ensure that every statement made was accurate and honest. I was regularly consulted throughout the editing process on the smallest details; a real eye-opening experience for me which left me impressed. The main History Channel may have thrown history aside for Ice Road Truckers and Pawn Stars, but their sister channel clearly is still doing their best to present accurate, interesting history (albeit on a tiny budget).

If you looks close, you will notice that I am constantly on the verge of being drenched in sweat; it turns out that the air conditioner of the bed and breakfast where the interview was shot was as loud as an F15 fighter jet at 10 paces. The interview was conducted in fits and starts: we would turn the AC on full blast for 10 minutes; then turn it off and try to get as much interviewing done before Niagara Fall began unleashing across my brow… then we’d start the process all over again.

Watch the television documentary

Watch the entire television documentary below. Access is restricted to registered members of baader-meinhof.com who would like to view the special for research purposes. Baader-Meinhof.com does not own this documentary and requests all who view it to seek out a random show on History International TV and watch the entire show, paying extra attention to the commercials, as a way to balance the karma equation.

Bambule [Registered]

A film written by Ulrike Marie Meinhof

Directed by Eberhard Itzenplitz

1970 – Südwestfunks Public Broadcaster

The television film “bambule” is intricately connected to the history of the Baader-Meinhof group; its deep connection is what turned this minor TV film film into one of the great “lost” films for almost 25 years. (The lowercase “b” was apparently intentional).

The film, produced by Stuttgart’s regional public broadcaster Südwestfunks, was set to appear across Germany on May 14, 1970 on the ARD public broadcasting network. But the film was pulled from the schedule because the writer of the film, Ulrike Meinhof, had become Germany’s most wanted fugitive four days earlier for her role in helping break convicted arsonist Andreas Baader from police custody in Berlin. What had been an effective and evocative portrait of life in a girls reform school, became political nitroglycerin; untouchable and locked in the Südwestfunks archives for decades.

Bambule tells the story of girls from society’s margins, confined to a state boarding home. The conditions of their care leads to an uprising amongst the girls; though eventually the uprising fails and the girls find themselves even worse off then before.

It was a shame that bambule became so closely associated with Meinhof and her actions; because by all accounts the film accurately detailed the oppressive and reactionary conditions in girls homes at the time. It was intended to provoke, and surely had it appeared on TV in 1970 it would have helped spur a debate (ultimately German laws were reformed in the 1970s, eliminating many of the abuses documented in the film).

The film represents a bit of a challenge for a casual German speaker; many of the actors were former and current residents of Berlin girls homes; all spoke in the peculiar and idiosyncratic idiom common to the residents of these homes. Even for a typical German the language is often hard to follow; though it adds considerable “realism” to the presentation.

In 1994, state public Broadcaster ARD finally decided it was time to pull bambule out of mothballs and show it to the world (Meinhof’s screenplay for the film had been published by Verlag Wagenbach in 1971). The 1994 broadcast is, so far, the only public showing of the film; and it has never been released on VHS, DVD, or Blu-ray.

Watch the movie

Watch the entire movie below in it’s entirety. Do you speak German and English and want to help out? Help translate Bambule so I can add English subtitles. Even if you took a five minute chunk it would be greatly appreciated!

Baader

Information coming soon

Marianne and Juliane

Die Bleierne Zeit (“Marianne & Juliane,” as this film is known in America) tells the story of two German sisters, one a journalist and the other a terrorist. The story is closely based on the life of Gudrun Ensslin and her sister Christine. The story is fictionalized, but it so closely resembles the life of Ensslin that one is tempted to view it as a bio-pic (in fact, the film is dedicated to Christine Ensslin).

A tremendously moving, thought-provoking film. The director Margarethe Von Trotta had a hand in two other very important Baader-Meinhof era films: she co-directed The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (“Die Verlorene Ehre der Katharina Blum”) with her now ex-husband Volker Schlöndorff, and she wrote a segment for the compilation film Deutschland im Herbst.

This movie is extremely hard to track down with English subtitles (as of the mid 2000s it’s available used as a VHS tape through Amazon for about $100). A dvd of the production is available from Amazon.de (Germany Amazon) in our store, but I don’t believe it contains English subtitles.

The Third Generation

The director of The Third Generation (“Die Dritte Generation”), Rainer Werner Fassbinder, was friends with Andreas Baader during their teenage years. Fassbinder was also generally considered a left-wing director, so this film must have come as a jolt to those expecting to find a film supportive of terrorist causes.

Die Dritte Generation is pessimistic enough to concoct a grand coalition between terrorists and the wealthy power brokers; the kidnappings and attacks are merely jointly coordinated fodder for dada-esque jokes on society. Coming only about a year after the kidnapping and brutal murder by the Red Army Faction of Hanns-Martin Schleyer, this film must have disturbed many people by presenting a Schleyer-like character that actually helps plan his own kidnapping for fun.

This film departs from the typical Douglas Sirk-style melodrama that populate Fassbinder’s career, but equals those films in quality. Fassbinder was never anything less than shocking, and he doesn’t disappoint with this film.

The Legend of Rita

This is an excellent film. Schlöndorff continues his fascination with the Baader-Meinhof/RAF era with this film telling the story of a group member who goes into hiding in East Germany during the 1980s. The movie is a fictionalized composite of many characters and incidents; it never refers to the group as the “Baader-Meinhof Gang” or the “Red Army Faction”. But the film is a highly accurate accounting of the types of people and incidents of the era.

It opens with Rita (actually a fictional name she is later given to conceal her past) and other members helping to break a group leader out of prison, followed by life on the run in Germany and France. Finally Rita and other members slip into the Democratic Republic, where they live out their lives in the anonymity of that countries grand socialist experiment. Idealistic Rita is treated with contempt and derision by many of her new co-workers, who cannot believe that she so blindly supports the East German state. [spoiler alert!] a co-worker realizes that she is in fact a former terrorist, and Rita is moved to another job in another city. At the point when her life seems to be coming together, East Germany is falling apart. Rita again goes on the run from West German authorities; she is killed as she runs a roadblock. [end spoilers!]

Much of the film is accurate: As if the world needed more damning proof of the evil corruptive nature of the East German state of the 1980s, East Germany did in fact take into hiding 11 former Red Army Faction members. Stasi officials even provided training (including Rocket Propelled Grenade training) to several of the members who returned to West Germany to commit more terrorist acts. The film was received poorly among many in the former East Germany who felt that the film took too many digs at easy targets like Trabant cars, glum workplaces, and glum workers.

Though I didn’t live in East Germany, I think the film is reasonably accurate and fair on East Germany; the negative comments are probably the inevitable wincing of people that are not far enough removed from the time period. Schlöndorff’s commentary track on the DVD is absolutely first-rate, and offers incredibly rich detail and historical background.

The English translation of the German title is the excellent “The Silence Before the Shot.” For whatever reason, the American distributors chose instead to call the film the infinitely dumber “The Legend of Rita,” continuing a tradition of taking interesting German titles and turning them into lame English titles.

The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum

The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975) is an early film that addresses the Baader-Meinhof era. Based on a noted novel by Nobel Laureate Heinrich Boll, the film focuses on the repressive atmosphere created by the sensationalist press in Germany.

The book and film were produced at the height of the Baader-Meinhof-era and as such are remarkable documents of the time. The story follows a maid who spends the night with a radical bank robber and possible terrorist (though she was unaware of it at the time). She helps him evade police custody after their night together. After the police question here, the press hounds her and essentially ruins her life.

With 30 years of perspective, one can easily look at this film (and the source book) as perfect reflections of what was going on in the mind of leftists in Germany at the time. Because the horrific bombings and murders in the spring on 1972, few leftists could realistically offer any type overt support for the activities of the group. But the overbearing and oppressive response to the Baader-Meinhof Gang by the hated Springer Press and the German state provided leftists an opening for taking up the cause without directly supporting or endorsing the activities of the terrorists.

Unfortunately this leaves us with a film and a book that essentially set up a straw-man argument. Katharina Blum, the young maid, IS almost completely innocent. Save for her assisting her new love evade the police, she does essentially nothing wrong to cause all of the grief that is heaved upon her. It would be virtually impossible not to feel sorry for her. And the film (and book) even manage to ultimately make her new boyfriend just a simple safe robber and not quite the dangerous radical that the police claimed he was.

It’s a quite effective film, but I’m left wishing for a film about many of the leftists who provide their homes, their money, and their cars over the years to various members of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, knowing full well who they were and what they were accused of. It would be interesting to explore the dynamic between these people, and the grateful urban guerrillas, who would nevertheless quickly blackmail some of these helpers into letting them stay longer because the helpers were now “aiding terrorism.” And it would be interesting to explore what went on in the mind of the man who ultimately turned in Meinhof to the police while she was hiding in his home. Compared to these people, Katharina Blum is the Virgin Mary.

When Blum kills the Bild-like reporter after he effectively destroys her life, it must have felt good to audiences sick of the years of sensational right-wing screeds from the hated Bild newspaper, it must have felt good for Heinrich Boll to write the scenario, and for the brilliant Volker Schlorndorff to direct it. But, with three decades of hindsight, it seems a bit unfair to create a false scenario, and then get all sanctimonious about that scenario.

The Criterion Collection of the DVD is terrific (look for a shout out to this website in the liner notes). It features a commentary by Schlorndorff and lots of extras. Really a terrific package for one of the most essential movies of the Baader-Meinhof era.

Stammheim

Stammheim is a fairly remarkable 1986 film about the trial and imprisonment of the leaders of the Red Army Faction. It was written by Stefan Aust and appeared shortly after his masterwork, “Der Baader-Meinhof Komplex” was published.

Stammheim follows the trial very closely and clearly hews tightly to actual transcripts of court proceedings. Like “The Baader-Meinhof Komplex” film of 2008 (also based on Aust’s work), this film doesn’t really formulate an opinion about whether Meinhof, Ensslin, Raspe, and Baader were murdered. But it is also much less explicit than the later movie in showing how it was clearly possible (and maybe even likely) that the prisoners killed themselves.

The actors are uniformly excellent; particularly Therese Affolter as Meinhof.

Like virtually every movie that touches on the Baader-Meinhof era, this movie was controversial upon release. It was screened at the Berlin International Film festival and the judges were starkly drawn over the movie; ultimately a divided judging corps awarded it the Golden Bear.

This film is currently only available in Germany; I don’t believe that it has English subtitles on the DVD release, but I might be mistaken.

Der Baader-Meinhof Komplex

“The Baader-Meinhof Komplex ” is a stunning 2008 film by Uli Edel, chronicling the rise and fall of the Baader-Meinhof Group.

Nominated for a Golden Globe and Oscar for Best Foreign Language film, the movie was based on Stefan Aust’s masterful book “The Baader-Meinhof Komplex.”

The film stars some of the most famous and prominent German stars like Moritz Bleibtreu, Alexandra Maria Lara, Martina Gedeck, and Bruno Ganz. The film was directed by Uli Edel, who first came to notice with the harrowing “Christiane F.” 30 years ago.

For students of the Baader-Meinhof era, this film is nothing less that remarkable. It’s surprising that it has taken more than three decades to produce a film that simply tells the full story of the era rather than tiny slices or as fictionalized accounts. There have been many other films that have explored the effects of left-wing terrorism, from the “Lost Honor of Katharina Blum,” to “Marianne and Juliane,” to the “Legend of Rita.” But they were all fictionalized aspects of small parts of the story. There was 2002’s “Baader,” but it was fatally flawed by altering the historical record by having Andreas Baader die in a shoot-out in 1972. So the “Baader-Meinhof Komplex” is a welcome entry in the long history of films inspired by the era.

People who know the story and era intimately might be put off mildly by some of the films anachronisms: the BMW 2002tii driven by Petra Schelm before she was shot was clearly a 1973-76 model that couldn’t have existed when she was shot in the spring of 1971, Gudrun Ensslin is shown watching the Berlin June 2, 1967 riot on TV, when she actually participated in the riot, etc. But ultimately these are very minor problems for a film that seems to have imported the early 1970s wholesale onto celluloid. It’s truly stunning.

Bleibtreu in particular is outstanding as Baader. He’s charismatic, appealing, and mean; sometimes all at once. Martina Gedeck is equally outstanding as Ulrike Meinhof. Some of the actors bear uncanny resemblances to their historical counterparts and others not-so-much. But overall each actor seems to channel the era beautifully.

The film does not skimp on detail; it thankfully avoids streamlining the story too much. It’s all there: from the attempted murder of Rudi Dutchke, to the rescue of Meinhof’s children by Stefan Aust, to the vacations on the Sylt resort, it’s amazing how many different elements to the story have been brought into this two-and-a-half hour film.

The film generated controversy when it opened in Germany and later in the UK; critics felt that it glorified terrorism. It’s an interesting argument. The film tells the story straight; but the story itself is clearly exciting. Is it the film that is glorifying terrorism or is it something inherent in the nature of the subject? I think of Francis Ford Coppolla, who made Apocalypse Now as the ultimate anti-war film, and proudly claimed that he designed it to make such a profound statement against war that those watching it would be rendered pacifists. Of course it had the opposite effect; soldiers in the first Gulf War and current Iraq war routinely would watch the “Ride of the Valkries” scene prior to going into battle in an effort to psyche themselves up for the conflict (see “Jarhead” for a recreation of just such a scenario). Perhaps any film made with care about terrorism would “glorify” terrorism to those inclined to become excited by the subject. Either way, it must be incredibly painful for the families of the victims of the Baader-Meinhof Group to see this group become prominent once again.

The Baader-Meinhof Komplex delves into another controversial area; what happened on “Death Night,” when Andreas Baader, Jan-Carl Raspe, and Gudrun Ensslin turned up dead in their prison cells? Like the book “Der Baader-Meinhof Komplex” that served as the basis for this film, the movie hedges on an answer. The great achievement of Aust’s book was not to say whether the prisoners killed themselves or were murdered by the state, the achievement was to show how it was possible and even likely that they committed suicide. But he couldn’t or wouldn’t say for certain that it was suicide and the film follows this line exactly. It’s probably the right take for such an immensely problematic matter. Interestingly, in Aust’s recently revision to his 1988 classic book, he drops much of the hedging and simply calls the deaths suicide. But the filmmakers were clearly more conservative.

If there is a one flaw of the film–an artistic choice, really–it is the breadth of characters that come and go in the film without any introductions. Bernd Eichinger, who wrote and produced the film, pointedly wanted us to be immersed into this world and often a bit confused as to whom we are seeing. I guess it adds a note of verisimilitude; but even I found myself confused as to which character was which at certain points–and I probably know these people as well as anyone on the planet.

The Baader-Meinhof Komplex was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film; it lost to a frankly inferior Japanese film.

December 21, 1975 Vienna

An all-star cast of terrorists, led by the infamous Carlos the Jackal, bursts into a OPEC conference. Among the terrorists were Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann, the Movement 2 June member who had been released as part of the Lorenz kidnapping, and Hans-Joachim Klein, a member of the little-known German terrorist group Revolutionary Cells, who had served as Jean-Paul Sartre’s chauffeur when he visited Baader in Stammheim. Kröcher-Tiedemann kills two men in the raid, an Austrian policeman Anton Tichler, and an Iraqi guard, Khafali. Carlos kills a Libyan civil servant, Yousef Ismirli. Klein is seriously wounded in the mêlée, but the operation otherwise works out well; Carlos secures $5 million ransom for Palestinian causes and the terrorists are able to disappear into the Middle East.

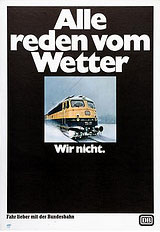

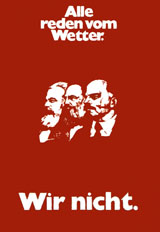

Mid-Summer, 1975 West Berlin

Members of the Movement 2 June steal thousands of U-Banh (subway) tickets and freely distribute them to grateful Berliners upset at recent price hikes in the tickets. Movement 2 June members also participate in two bank raids in which they distribute chocolate kisses to the customers and bank staff.

By September, however, most of the Movement 2 June leadership is in jail: Ralf Reinders, Till Meyer, Inge Viett, Julianne Plambeck, Fritz Teufel, and Gabrielle Rollnick. They are all charged with the Lorenz kidnapping and the bank raids. Reinders is charged with the murder of von Drenkmann in November of the previous year.

August 19, 1975, Stuttgart

The defendants are finally officially charged: Gudrun Ensslin, Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof, and Jan-Carl Raspe are jointly charged with four murders, 54 attempted murders and a single count of forming a criminal association.

June 23, 1975 Stuttgart

Croissant and Ströbele are arrested and Croissant’s Stuttgart offices are raided.

June 5, 1975 Stuttgart

Baader begins the second day of hearings by reminding the court that is still without representation. He also makes the bold claim that the cells are bugged. His suspicions are dismissed out of hand by the skeptical German press; Baader is getting paranoid, they say.

Two years later the existence of the bugs will be admitted by government authorities. They will claim that they only monitored the bugs briefly during the Stockholm Embassy stand-off, and again briefly in 1976. Supposedly the authorities immediately erased all of the tapes; no copies will ever turn up.

May 21, 1975 Stuttgart

The pretrial hearings of the Baader-Meinhof leaders begins in the newly constructed Stammheim prison courtroom. Utilitarian in nature, the courtroom was constructed on the grounds of Stammheim prison at a cost of DM 15,000,000. The roof is covered with jagged razor wire to prevent helicopter landings and steel nets to prevent any potential airborne bombs from doing damage, the entrance has a sophisticated metal detector.

Otto Schily, Marielouise Becker, Rupert von Plottnitz, and Helmut Riedel are present as defense lawyers, but Baader is still without representation with the expulsion of Croissant, Ströbele and Groenwald. Several state appointed defense lawyers are present as well. Judge Theodor Prinzing is the lead judge of several judges that jointly oversee the trial.

Mid-May 1975, Stuttgart

Technicians from the Federal Intelligence Service install two more bugs in two unoccupied Stammheim cells; now seven Baader-Meinhof prison ward cells are bugged.

April 24, 1975 Stockholm

Six Red Army Faction terrorists, most of whom were former members of the Heidelberg Socialist Patients Collective (SPK), take over the West German Embassy in Stockholm, taking 11 hostages. The terrorists are: Siegfried Hauser, Hanne-Elise Krabbe, Karl-Heinz Dellwo, Lutz Taufer, Bernhard-Maria Rössner, and Ullrich Wessel. Swedish police quickly occupy the lower portion of the embassy. The terrorists order them to leave, saying they will kill the military attaché if the police don’t comply. They don’t. Angry, the terrorist bind the hands of the embassy’s military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel Baron Andreas von Mirchbach, and order him to walk toward the top of the stairs of the upper floor. Then they shoot him in the leg, head and chest. Police drag the dying man away (after stripping down to their underwear to show that they were unarmed) and then move out of the building.

The terrorists pile massive amounts of TNT into the basement of the facility, and then call the German Press Agency and list their demands. The want all Baader-Meinhof defendants released immediately. This time Bonn does not respond quite as favorably as they did during the Lorenz kidnapping. The kidnappers indicate that they will begin shooting a hostage every hour until their demands are met. After one hour Dr. Heinz Hillegart, the embassy’s economic attaché is taken to an open window. A terrorist shoots him and leaves the elderly Hillegart’s body hanging like a rag doll out of the window.

Shortly before midnight a wiring short causes the TNT to explode prematurely. Ullrich Wessel is killed immediately, but all of the other terrorists and hostages survive, most with bad burns. All of the terrorists are captured without a fight. Terrorist Siegfried Hausner is particularly badly burned, and is flown to Stammheim Prison’s medical ward a few days later. He dies in prison on 5 May.

The terrorists in the operation had been handpicked by Siegfried Haag, the lawyer associate of Klaus Croissant. With the imprisonment of the leaders of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, Haag has become the de facto leader of the so-called “second generation of the RAF,” which is dedicated almost solely to freeing the first generation’s leaders from prison.

April 15, 1975 Karlsruhe

Four American lawyers formally protest the “Baader-Meinhof Laws” in Germany’s Constitutional Court: former US Attorney General Ramsey Clark, radical “Chicago Seven” lawyer William Kunstler, powerful leftist lawyer Peter Weiss, and William Schaap.

Their protests do little good. The court approves the laws, allowing the Baader-Meinhof judges to exclude Klaus Croissant, Kurt Groenwald, and Hans-Christian Ströbele from the defense team. These moves are ironic because Croissant, Groenwald, and Ströbele have all been recently kicked off of the defense team already by the Baader. The Baader-Meinhof defendants clearly want it known who was in control, and any perceived ideological weakening of one of their lawyers resulted in the sacking of that lawyer.

March 8, 1975 Aden

Press reports indicate that leftist South Yemen government has asked the freed terrorists to leave their country, apparently from pressure by West Germany.

March 6, 1975 Paris

A bomb rips through the Paris offices of Axel Springer’s newspaper chain, destroying it. A Paris news agency receives a typewritten note from “the 6 March group,” claiming that the bombing was committed to demand “the liberation and total amnesty of the Baader-Meinhof group.”

March 4, 1975 Frankfurt am Main & Berlin

Heinrich Albertz and the rest of the Lufthansa crew fly back to Frankfurt from Aden, South Yemen, having released Pohle, Becker, Heissler, Siepmann, and Kröcher-Tiedemann (who had a second change of heart and elected to make the trip after all).

A car screams through Berlin’s Wilmersdorf district shortly before midnight. Lorenz is pushed out of the back seat, his blindfold removed, and given a 50-fenning coin. He stumbles over to a phone booth as the car tears off. Lorenz calls his wife and lets her know that the ordeal is over. Within minutes police begin raiding suspected radical hideouts throughout Berlin and the Federal Republic.

March 1-3, 1975 Stammheim Prison

Bugs are secretly installed in five of the Baader-Meinhof cells at Stammheim prison, by the Counter-Espionage unit of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution.

March 1, 1975 West Berlin

Newspapers worldwide print the image of Ettore Canella sprinting to freedom out of his Berlin jail. Behind him, Gerhard Jagdmann strolls out assuredly.

During their evening broadcasts, the German news programs show interviews with Gabi Kröcher-Tiedemann from her Essen jail cell, and Horst Mahler from his Berlin cell; both refuse to be released, electing to stay in prison.

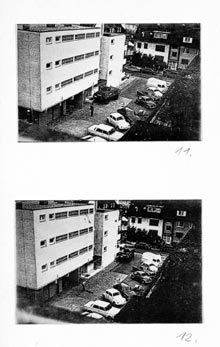

February 28, 1975 West Berlin

A Polaroid photo is released early in the morning showing Lorenz with a sign around his neck: “Peter Lorenz, prisoner of the 2 June Movement.” With the photo is a demand for the immediate release of six terrorists: Horst Mahler, Verena Becker, Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann, Ingrid Siepmann, Rolf Heissler, and Rolf Pohle. Except for Mahler, all are either members of Movement 2 June, or connected to it. A message is attached to the demands: “to our [Baader-Meinhof] comrades in jail. We would like to get more of you out, but at our present strength we’re not in a position to do it.” The kidnappers have been careful in making their selections; no terrorist accused of murder is on the list.

28 February 1975, Berlin – “Peter Lorenz, captive of Movement 2 June” reads the Polaroid photo sent to police the day after the capture of Lorenz, the CDU Berlin mayoral candidate.

The kidnappers demand that authorities provide a Boeing 707 within three days. Three of the prisoners, Pohle, Kröcher-Tiedemann, and Heissler, must be flown from their jails throughout the Federal Republic to Berlin within two days. The others are already in Berlin. When all six are ready to fly on the 707 to a country of their choice, they are to be given $9,000 each. Furthermore, the kidnappers want former Mayor Heinrich Albertz to accompany their jailed comrades on the flight to guarantee their passage. Albertz was the mayor who initially condemned the rioting during the Shah visit on 2 June, 1967, but was ousted after he had a change of heart. Albertz agrees to participate, but only in his role as a Protestant pastor, and not in his role as a former politician.

The kidnappers also demand the unconditional release from a Berlin prison of a couple of small-time left-wing protestors, Ettore Canella, an Italian, and Gerhard Jagdmann, who both were arrested for protesting during the previous November.

February 27, 1975 West Berlin

At about 9:00 AM, Peter Lorenz leaves his home in the Zehlendorf district. Lorenz is the CDU (Christian Democrat Union) candidate for mayor in the West Berlin city elections to be held in three days. Less than half a mile from his house, his Mercedes is blocked by a large truck, and a Fiat rams his car. Lorenz’s driver, Werner Sowa, is beaten, and Lorenz is kidnapped into a waiting automobile. The kidnappers are from Movement 2 June. Sowa identifies Angela Luther, who has been underground for three years, as one of the kidnappers.

Authorities put up a $44,000 reward for information. Current Berlin Mayor Klaus Schütz (Lorenz’s SPD opponent and a personal friend of Lorenz’s) announces that the elections will take place as scheduled, but all campaigning will be called off.

January 1, 1975 Bonn

“Lex Baader-Meinhof,” or the “Baader-Meinhof Laws” become effective. These laws, which are amendments to the “Basic Law,” West Germany’s quasi-constitution, allow the courts to exclude a lawyer from defending a client merely if there is suspicion of the lawyer “forming a criminal association with the defendant.” The new laws also allow for trials to continue in the absence of a defendant if the reason for the defendant’s absence is of the defendant’s own doing; i.e. they are ill from a hunger strike.

November 29, 1974 West Berlin

Ulrike Meinhof is sentenced to eight years imprisonment for her part in the 1970 freeing of Andreas Baader. Horst Mahler is given an additional 4 years (for a total of 12 years), and Hans- Jürgen Bäcker is found not guilty.

Late November, 1974 Cologne & Stuttgart

Former student leader, “Red” Rudi Dutschke, visits Jan-Carl Raspe in Ossendorf prison. Dutschke’s young son, Hosea-Ché Dutschke (named after a biblical character and Ché Guevara), tags along. Raspe is transferred to Stammheim shortly thereafter.

Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (center) interviews Andreas Baader in Stammheim Prison at Ulrike Meinhof's request. On the left is Baader-Meinhof lawyer Klaus Croissant, and on the right is Sartre's driver in Stuttgart, Hans Joachim Klein, who later goes underground after joining in terrorist actions with "Carlos the Jackal."

At Meinhof’s urging, Baader-Meinhof lawyer Klaus Croissant convinces famous French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre to visit Andreas Baader in prison. His chauffeur in Stuttgart is Hans Joachim Klein, who will participate two years later with Carlos the Jackal in the terrorist take-over of the yearly OPEC ministers meeting.

November 9, 1974 Wittlich

Holger Meins, a tall man of 6 foot 4, dies after starving himself on a hunger strike. His weight at death was 100 pounds. Revolutionary Cells terrrorist Hans-Joachim Klein would say of this photograph: "I have kept this photo in my wallet to keep my hatred sharp."

Holger Meins lays dying in his Wittlich cell. A tall man, he now weighs less than 100 pounds. His lawyer, Siegfried Haag, visits him in jail and realizes that he is dying. By 5:00 PM, Holger Meins is dead.

October 2, 1974 Stuttgart

The five primary members of the gang, Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof, Gudrun Ensslin, Jan-Carl Raspe, and Holger Meins, are indicted officially of dozens of crimes, including murder. Baader is transferred to join Ensslin in Stammheim (Meinhof is still on trial in Berlin). Holger Meins, whose physical health has been severely weakened by the hunger strike, stays in his Wittlich jail cell. All of the prisoners continue their hunger strikes, though there is evidence to believe that a few of the prisoners, like Baader, are cheating. Prison officials begin force feeding Ensslin and Meins, strapping them to tables, opening their mouths with pry-bars, and forcing feeding tubes down their throats.

September 1974, Federal Republic of Germany

A document from some of the imprisoned group leaders, explaining the reasons for their hunger strike, is smuggled out of prison by defense lawyers and released publically.

Mid-year 1974, Federal Republic of Germany

The Urban Guerrilla and Class Struggle,” an official history and manifesto of the Red Army Faction, is written by Meinhof (with major editing by Ensslin) and released.

June 4, 1974 West Berlin

Ulrich Schmücker of Movement 2 June is shot dead in a Berlin park by members of the group, reportedly because he was an informant. According to Stefan Aust, the death may have been an accident; the result of a mock death sentence gone awry.

Ulrich Schmücker, a member of the June 2nd Movement, is shot by his fellow terrorists in the Grunewald, the large forested park on the Western edge of Berlin’s Dahlem neighborhood. Some believe Schmücker was executed because his fellow terrorists believed that he was an informant, others believe that he was accidentally shot during a “mock” execution designed to scare him.

A lawyer for the Socialist Patients Collective, Eberhard Becker, is arrested.

April 27, 1974 West Berlin

Meinhof is transferred temporarily to Berlin’s Moabit prison to be tried for her part in the May 1970 freeing of Andreas Baader. Meinhof is tried with Horst Mahler, who is already serving time for his part in the crime (he had previously been found Not Guilty of participation, but the verdict was set aside), but is now being tried for “criminal association, and Hans-Jürgen Bäcker, who at the time was believed to be the gunman who shot the elderly librarian Georg Linke in the 1970 rescue of Baader.

Meinhof uses her courthouse pulpit to announce another hunger strike among the prisoners. Mahler declines to take part in the hunger strike, thus essentially confirming that he is no longer a member of the RAF. His former associate Monika Berberich denounces him on the Moabit stand: “[Mahler is an] unimportant tattler and a ridiculous figure.”

April, 1974 Stuttgart

Ulrike Meinhof and Gudrun Ensslin are transferred to Stuttgart’s Stammheim prison. They are the first residents of Stammheim’s newly refitted high-security wing. The plan is for all of the major Baader-Meinhof defendants to ultimately live in Stammheim. Plans are set in motion to build a large, self-contained courthouse in the potato field beside Stammheim prison. The courthouse, costing millions, is to be built especially for the pending Baader-Meinhof trial, and then converted for prison use.

February 13, 1974 West Berlin

The trial for the bombing of Berlin’s British Yacht Club by members of the Movement 2 June begins. Verena Becker, Wolfgang Knupe, and Willi Rather are the defendants. Students and radicals riot outside the courtroom.

February 5, 1974 Cologne

Gudrun Ensslin is transferred from Essen to Cologne’s Ossendorf prison, and placed into the cell next to Ulrike Meinhof.

Richter Cycle: Funeral

Title: Beerdigung

1988. Oil on Canvas

200 cm X 320 cm

This largest painting of the cycle is of the massive funeral of Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, and Jan-Carl Raspe in a Stuttgart cemetery a week after their deaths in Stammheim prison in 1977. Ensslin’s father had struggled to find a cemetery that would allow him to bury his daughter. Manfred Rommel, the popular mayor of Stuttgart (and son of war hero Irwin Rommel), unilaterally decided that the terrorists must be allowed to be buried in a Stuttgart cemetery. “After death, all enmity must cease,” said Rommel.

Richter Cycle: Dead 1, 2, 3

title: Tote, 1, 2, und 3

1988. Oil on Canvas

62 cm X 73 cm

These three paintings are alternately-sized versions of the same source photo. The original image is of the dead body of Ulrike Meinhof, who hung herself in her Stammheim prison cell on Mother’s Day in 1976. The original image is shocking, graphic, and gruesome; her neck having been cut through by the home-made cord she used to end her life. These images are also unique in the cycle; they represent an event that occurred more than a year before October 18, 1977. They contrast sharply from the warm, wistful image of the first painting in the series, a glamour shot of a younger Ulrike Meinhof.

Richter Cycle: Man Shot Down 1 & 2

title: Erschossener 1 und 2

1988. Oil on Canvas

100.5 cm X 140.5 cm

These two paintings feature alternate versions of an image of a dead Andreas Baader in his Stammheim prison cell. The official version of Baader’s death claims that sometime in the night of October 17 and early in the morning of October 18, 1977 (between 11:00pm and 7:00am), in cell 719 Baader removed his carefully hidden 7.65 caliber FEG pistol from its hiding place (it was among the dozens of illegal items smuggled into the “most secure prison in the world” by Baader-Meinhof lawyers). He shot two bullets: one at the wall and one into a pillow, to leave the impression of a fight. Then he held the gun behind his neck, put his thumb on the trigger, and pulled it, blowing a hole through the top of his forehead.

This official explanation has never been accepted by many on the left.

Richter Cycle: Record Player

title: Plattenspieler

1988. Oil on Canvas

62 cm X 83 cm

This painting is based on a photograph of Andreas Baader’s phonograph taken after his death. Left on the phonograph is side two of Eric Clapton’s “There’s One in Every Crowd,” on RSO Records (if you look closely you can make barely make out the famous RSO Records’ red cow logo).

Original Source Image

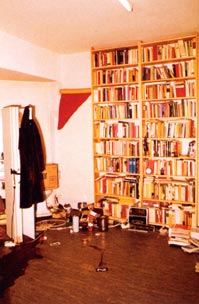

Richter Cycle: Cell

title: Zelle

1988. Oil on Canvas

201 cm X 140 cm

This painting depicts Andreas Baader’s cell in Stammheim prison as it was found after Death Night. Among many, the popular image of Baader was of a poorly educated poseur, more interested in violence than theory. Though Baader may have come to his revolutionary career without a formal background in Marxist thought, by the end of his life his knowledge had become deep and real. The hundreds of books lining Baader’s shelves were a testament to Baader’s intellect.

Original source image

Richter Cycle: Hanged

title: Erhängte

1988. Oil on Canvas

201 cm X 140 cm

This haunting image is of the dead body of Gudrun Ensslin, hanging from her Stammheim prison cell. It is the first image of the cycle to directly depict events from October 19, 1977, also known as Death Night. According to the official version of events, upon hearing of the storming of a hijacked Lufthansa plane by German GSG-9 counterterrorism forces, Ensslin took a speaker wire, threaded it through the wire mesh of her window, formed a noose, put it around her neck, and kicked aside the chair that she was standing upon.

Richter Cycle: Confrontation 1, 2, 3

title: Gegenüberstellung 1, 2, und 3

1988. Oil on Canvas

112 cm X 102 cm

These three images are of Gudrun Ensslin, girlfriend of Andreas Baader, and the true female leader of the Baader-Meinhof Gang. The images come from full-body images taken when Ensslin was in police custody. I believe that they are from photos taken of Ensslin as she is entering the courthouse built on the the grounds of Stammheim prison, especially for the Baader-Meinhof trial.

Richter Cycle: Arrest 1 & 2

title: Arrest 1 and Arrest (Festnahme 1 und 2)

1988. Oil on Canvas

92 cm X 126.5 cm

These two paintings are derived from images seared into the minds of most Germans who came of age in the 1970s and before. They are from the capture of Andreas Baader, Jan-Carl Raspe, and Holger Meins in a Frankfurt neighborhood on June 1, 1972. All of Germany was riveted to their television sets that day as the terrorists were holed up for the better part of a day in a garage. Raspe was captured early, but Baader and Meins managed to escape into the garage. A sniper shot Baader in the leg, convincing Meins to surrender. He is told to strip naked, ensuring that he held no grenades or guns under his clothes. Later the police storm the garage, pulling a wounded Baader out. Most Germans alive at the time can still picture a wounded Baader being pulled in a gurney, still wearing his fashionable Ray-Ban sunglasses.

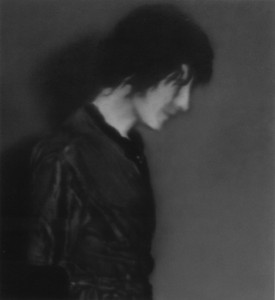

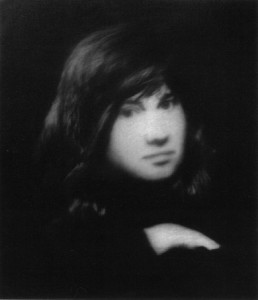

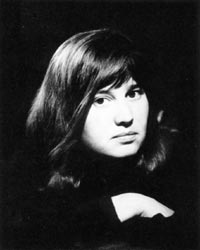

Richter Cycle: Youth Portrait

title: Youth Portrait (Jugendbildnis)

1988. Oil on Canvas

72.5 cm X 62 cm

Youth Portrait is derived from a photo of Ulrike Meinhof that had been mistakenly identified by Richter and others as a youth “glamour” photo of Meinhof. According Robert Storr’s MOMA book about the exhibit, Meinhof’s former husband Klaus Rainer Röhl indicates that the photo was actually a publicity photo taken in anticipation of the 1970 release of her telefilm “Bambule,” when Meinhof was 36 years old.

Interview with Director Bruce LaBruce

Director Bruce LaBruce uses the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon as a jumping-off point to explore the commodification of the German radical terrorist movement in his latest film “The Raspberry Reich.” After a successful circuit of many of the world’s most famous film festivals, including Sundance, the Berlinale, and the Seattle International Film Festival, “This is Baader-Meinhof” creator Richard Huffman talks with LaBruce.

Richard Huffman Tell me a bit about yourself, your background as a filmmaker, and your filmmaking philosophy.

Bruce LaBruce After growing up on a farm in Canada, I moved to Toronto to attend film school at York University. I started out in production, but transferred after two years to theory and went on to receive a Masters in film and social and political thought. While I was working on my thesis (on Hitchcock’s Vertigo) I became disillusioned with academia and started hanging out in the downtown punk scene. I began to make short experimental super 8 movies with explicit homosexual content in order to disrupt the sexual complacency of the punk scene at the time. With the advent of hardcore and speedcore, a certain machismo had creeped into punk, which included a strain of homophobia and sexism. I made provocative, sexually explicit fanzines and films to challenge the sexual conformity of these supposed radicals. My first feature length movie, No Skin Off My Ass, about a gay hairdresser who falls in love with a neo-Nazi skinhead, was shot on super 8 and blown up to 16mm. It became a hit on the gay festival circuit.

My next two features, Super 8 1/2 and Hustler White, were shot on 16mm. They were also both sexually explicit art/punk movies. My latest two features, Skin Flick (hardcore version: Skin Gang) and The Raspberry Reich, were both made for porn companies. I consider myself an artist who works in porn. Up to this point with my movies I have been trying to carry on the tradition of homosexual avant-garde film-making, taking my cues from the likes of Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, George Kuchar, and Curt McDowell. I am also interested in following in the footsteps of other homosexual artists who made porn movies such as Peter Berlin, Jack Deveau, Wakefield Poole, Peter de Rome, and Fred Halsted. I like to make personal films, and I also consider my work “underground”, although increasingly, considering the co-optive powers of corporate media and the reach of the internet, there is no such thing.

Richard Huffman Tell me about “The Raspberry Reich”… why did you want to make this film?

Bruce LaBruce My previous movie, and first legitimate porno, Skin Flick/Skin Gang, was about a gang of neo-Nazi skinheads, representing the extreme right wing, who break into the apartment of a mixed race bourgeois gay couple and sexually terrorize and violate them. It was an investigation into why gays tend to fetishize authoritarian and fascistic figures (cops, skinheads, etc.), and the phenomenon of the prevalence of homosexuality amongst extreme right wing leaders and movements. With The Raspberry Reich I wanted to examine a gang on the extreme left wing – in this case a terrorist cell – to see if any of the sexual dynamics were similar. My last three movies, including Hustler White, which is about male prostitutes on Santa Monica Blvd. in LA, concern males who do not in any way identify themselves as gay but who nonetheless have homosexual sex with each other. I’m always interested in the idea of identity politics and the arbitrariness or artificiality of sex and gender roles. Most heterosexual men have fixed themselves in a rigid role which doesn’t even allow the possibility of bi- or homo-sexual impulses, even though many theorists, from Freud on, have posited the notion that everyone is born with at least some bisexual potential. Females seem to be a little more sexually fluid. Homosexual men have likewise fixed themselves in a gay identity which doesn’t allow the possibility of sex with females, sequestering themselves away in an all male environment and trying very hard not to think of the vagina. It’s clear that when heterosexual men are confined together under intense circumstances – the military, prison, etc. – that homosexual behaviour emerges quite easily. Similarly, in Muslim cultures, where men and women are often segregated, homosexuality is quite common, if strictly discrete and unacknowledged. So my films often explore this disconnect between sexual potential and rigid sexual behaviour based on cultural imperatives and preconceptions.

I became disillusioned with the gay movement very early on, even back in the mid eighties deciding that it had become politically stagnant, aesthetically bankrupt, and hopelessly bourgeois. (The current assimilationist trend toward sexual conformity, marriage, and respectability has certainly vindicated my point of view – the oppressed have demonstrably become the oppressors!) I turned to punk because it seemed to be challenging defiantly the status quo, the ascendance of corporate interests and control, and the attempts of the dominant ideology to police, dominate, and neuter all forms of dissent, otherness, and individuality. My first wake up call was realizing that even punk, this supposedly radical subculture, was sexually conformist. This led to an interest in other manifestations of social and political protest, including an investigation into the terrorist or para-military organizations of the late sixties and seventies such as the SLA, the Weathermen, the Black Panthers, and, of course, the Baader-Meinhof gang, the RAF. Each of these groups took very seriously the notion that Godard posited in his movie Numero Deux: le cul, c’est la politique: the sexual is political. They believed that revolution could only be achieved if it was accompanied by a radical rethinking of sexual mores and conventions. People forget nowadays that back then there actually was such a thing as a sexual revolution, when even members of the middle class were experimenting with promiscuity, group sex, bi- and homosexuality, communal living, sex and spirituality, etc. In university I had taken such courses as Protest Literature and Movements, and Psychoanalysis and Feminism, so I already had a background in the teachings of such thinkers as Reich, Marcuse, and other radical theorists who believed that sexual repression was responsible for much of the violence and apathy and spiritual malaise in technologically advanced cultures. I was also very interested in the way that emerging counter-cultural minorities of that era – particularly the black, gay, and feminist movements – adopted a kind of proto-military style and rhetoric, often borrowing from the kind of guerilla insurgencies that had emerged simultaneously in Central and South America. These movements were all initially Marxist-based, defiantly militant, and organized on a kind of decentralized, anarcho-syndicalist model. They emerged out of or gained momentum from the anti-Vietnam war movement and the strikes and student protests of May ’68, so they were geared towards labour and empowering the common people and predicated on notions of correcting social and political injustices and inequalities based on race, class, and gender. The platforms of the ultra left wing terrorist groups which emerged from this milieu were based on these humanist, egalitarian ideals. They believed, however, that any ends justified the means to achieve these goals, which placed them in morally untenable situations, eventually rendering them almost indistinguishable from their avowed enemies. (The oppressed becoming the oppressor is a theme that runs throughout my movies.)

With The Raspberry Reich I wanted to revisit these ideas and sentiments in a more modern context. After 9/11, particularly in North America, the left was castrated and rendered virtually silent. I wanted to make a movie that gave voice once more to the left wing, anti-corporate, anti-capitalist rhetoric that was once part of the public discourse but which had become completely absent. The movie also operates as a critique of the left, skewering people who either don’t practice what they preach, or who become so self-righteous and intractable in their beliefs that they themselves become oppressive and dogmatic.

The Raspberry Reich concerns an extreme left wing gang in Berlin who emulate the RAF. Gudrun is the leader of a band of impressionable, ostensibly heterosexual young men who are captivated by her radical ideas and energy. She believes, however, that heterosexual monogamy is a bourgeois construct that must be smashed in order to achieve true revolution, so she makes these straight boys have sex with each other to prove their commitment to the cause. This also just happens to be the perfect set-up for a gay porn movie.

Richard Huffman On your film’s web site, you describe The Raspberry Reich as “an art/porn film that, like all my films, uses pornography as a starting point to examine sexual politics and homosexual radicalism. (For me, working in pornography is like a genre exercise.)” On the flip side of this, to what extent was the subject matter of “radical chic” a starting point to examine sexual politics and homosexual radicalism? Could the radical chic storyline also be viewed as a genre exercise?

Revolution is my Boyfriend Daniel Bätscher is "Holger" and Susanne Sachsse is "Gudrun" in "The Raspberry Reich."

Bruce LaBruce I also made The Raspberry Reich in order to comment on the modern cultural tendency to co-opt and commodify the signifiers of radicalism and militancy without adopting any of their actual political substance, or worse, in the process, completely contradicting their original intent. In my movie one of the slogans is ‘Madonna is Counter-Revolutionary’, and I do mean that literally. As I always argue, Madonna is the exact opposite of someone like Jean Genet, whose strategy was to go immediately to any place in the world where there emerged a truly revolutionary impulse (the Black Panthers in America in the late sixties; the Palestinians in the Middle East in the seventies), but as soon as he detected the first sign of co-option or institutionalization, he would not only abandon the movement but turn against it. Madonna also zeroes in on revolutionary moments (usually gay and/or black subcultural manifestations), but with the strategy of co-opting, neutralizing, commodifying, and ultimately exhausting and abandoning them. She is the ultimate example of someone who uses radical chic for exploitative and purely capitalistic ends. In Germany there has been for four or five years a resurgence in interest in the RAF, but mostly as a kind of fashionable symbol, a signifier of hip, cosmetic rebellion similar to the phenomenon of Che Guevera being turned into the new James Dean or Marilyn Monroe. There was even a movie called Baader which turned Andreas Baader into a kind of hipster folk hero, all style and no substance. Groups like the RAF did have a certain glamour quotient in the seventies, with their leather jackets, berets, sunglasses, and fast cars, but their glamour then also came from their deep convictions in social and political causes and their commitment to carrying out actions against the state. Intellectualism was also considered glamorous in those days, as opposed to the current tendency to distrust and dismiss intellectual analysis. Their glamour had to do with a kind of Robin Hood mentality. With the ascendance of capitalism, crimes against property or theft are now regarded as worse than violent crimes or murder.

The Raspberry Reich is also meant as a kind of exploitation film, a genre that has long since been co-opted by Hollywood. (What are movies like Bad Boys or American Pie if not cheap exploitation on a large budget?) There was formerly a tradition of sexploitation movies, but also b-movies that included kidnap flicks, heist movies, caper movies, etc. I’m also referencing those genres.

Richard Huffman Much has been made about the gender and sexual politics of the Baader-Meinhof Gang; how they represented a manifestation of the free love ideal of the sixties and seventies; how men and women shared power. But I’ve never seen discussed the possibility or probability that some of the members of the group are or were gay (though shear logic would say that there must have been gay members). How do you think that the group would have been viewed by the “raspberry reich” at the time, and modern followers of “radical chic” had the group been outspoken at including a gay liberation element to their espoused philosophy?

Radicals Holger (Daniel Bätscher), and Andreas (Dean Stathis) hold Patrick (Andreas Rupprecht) hostage.

Bruce LaBruce Actually, in gay circles in Berlin it seems to be widely accepted that Andreas Baader started out as a male prostitute who frequented the bars in the Schoeneberg district, Berlin’s gay ghetto. During the making of The Raspberry Reich, a friend introduced me to Felix Ensslin, Gudrun Ensslin’s son, and we had dinner. I told him about the project, that it was an art-porno based on the sexual theories of Reich and Marcuse, and he seemed to think that the Baader/Meinhof would have been totally into the idea, and that they really did believe that the sexual was political and that sexual revolution was an important part of their agenda. When the RAF and other radical groups like the SLA and the Weathermen existed in the seventies, the tenor of the times was much different. Ideas of sexual liberation and the challenging of predominant sexual roles were much more commonly accepted and even practiced by the members of the middle class. A lot of the girls of the SLA were openly lesbian, and the Weathermen were into group sex and bisexuality. So I don’t think overt homosexuality would have made them any less compelling. I mean, Huey P. Newton of the Black Panthers famously reached out to include gays and feminists as part of the kind of revolution he envisioned. It’s interesting and kind of sad that the most popular black movement now, hip hop, routinely disrespects women and homosexuals. But then again, corporate hip hop is all about materialism and capitalist capitulation, as is the gay movement. Where’s the Baader/Meinhof when you need them?!

Richard Huffman As I’m sure you’re aware, Gudrun Ensslin made a porn film prior to her going underground. As I understand it, she did the film entirely in the spirit of the times; as much as a statement of sexual freedom as a way to secure money. Is there any basis of comparison for the actors in YOUR art/porn film? Did their motivations for participation go beyond the simple financial reasons?

Believe me, financial considerations were not part of their motivation. My movies are very low budget, so people aren’t doing it for the money. All of the male actors in the movie are porn actors, so they were just doing their job and didn’t really know what they were getting into until they got on set. They knew me by reputation and were interested in working with me. When they started to get the idea of the movie, they were quite into it. They were all smart and got what I was doing. The European attitude towards sex and porn is still very much more aligned with the spirit of sexual freedom that existed in America in the sixties and seventies. They’re very adult about it, and don’t seem to have a lot of the same hang-ups about porn that Americans have. I insist that everyone involved in my pornos know what they’re doing and why they’re doing it, and it’s a completely non-exploitative environment.

As for Susanne Sachsse, who plays Gudrun so beautifully, she is an established Berlin stage actress who was with the Berliner Theatre Ensemble for three years and has done Brecht and all that jazz. So for her it was very much about wanting to work with me as a director and challenging herself as an actress in a very difficult role. She is from East Berlin, so having been raised behind the Iron Curtain I think she understand the ramifications of the anti-capitalist Baader-Meinhof gang much more clearly than I did, and I learned a lot from her. (For me, the whole RAF phenomenon was, from a distance, somewhat abstract; it was only after I started making the movie in Berlin and meeting people directly affected by the RAF that it became something very real and concrete.) Susanne felt as an actress that it was important for her to “go the distance” and perform in a sexually explicit scene in the movie. I had told her that I would like her to do it, but it wasn’t a condition of her getting the role. It was entirely up to her. Part of the meaning of the film is to Put our Marxism where our Mouth Is and make it sexually real as a reinforcement of the ideals of sexual liberation being espoused by the movie. So Susanne was definitely in the spirit of not only the movie but the kind of radicalism that the movie is about.

Richard Huffman Who is your audience for the Raspberry Reich? I can imagine what it must be like for gay guys to sit through a steamy heterosexual porn film; it’s pretty hard for a straight guy to watch pretty much anything that is homoerotic. Seeing the trailer for the film, I assume that this is a strong element of the film; what do you anticipate the straight guy response to the film to be? Are you hoping to be provocative and challenging to straight guys about their sexuality?

Bruce LaBruce Generally in my movies I like to include something to offend everyone. I’m often surprised that there is an audience for my work at all. The art world often ignores me because they think I’m too pornographic, while the porn world resents me for being too arty or intellectual and interfering with their precious, pornographically pure product. I’m an interloper, a common adventuress. So far I’ve shown The Raspberry Reich in quite a few non-gay festivals – Sundance, the Berlinale, the Seattle International Film Festival, the Melbourne Underground Film Festival – and for the most part it seems to play well to straight(er) audiences. It does start out with a straight sex scene, so that may palliate some of the more nervous heterosexual male viewers. I definitely want the movie to reach straight male viewers. I’ve already noticed that it makes a lot of guys who review movies on the internet nervous. They go on and on at great length at how awful and terrible the movie is – it really seems to get under their skin. Perhaps I’m hitting a nerve. I hope so. Especially these supposed underground hipsters who think they’re so enlightened and progressive. It’s hard to get them out of the missionary position.

Richard Huffman By exploring the dynamics of this group of “radical chic” followers of the RAF, did you learn anything about the dynamics of the real Baader-Meinhof Gang? Meaning did any truths about how they must have operated become self-evident as you explored your fictional group?

Bruce LaBruce Well, my movie is about a group of very inept, would-be terrorists who emulate the Baader-Meinhof in a kind of comical way. I was referencing movies like Fassbinder’s The Third Generation, Godard’s La Chinoise, and Dusav Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism – agit-prop films that playfully illustrate revolutionary principles with narrative skits, direct camera address, or even documentary elements. My movie isn’t exactly supposed to be taken seriously as an investigation of the fundamental principles of terrorist abduction, but in a strange way, any time you make a movie, especially a low budget one, you become a bunch of urban guerillas. We worked completely without permits, shot in ad hoc locations without permission, shot people surreptitiously on the street without them knowing it, etc. We got kicked out of our location in a great old east berlin apartment building on Karl Marx Allee because the neighbours started to complain when they saw guys in ski masks holding guns running in and out of their building. So in a way it did approximate that kind of feeling of trying to evade the authorities and operate under the radar. Also when you make a movie you inevitably adopt this conviction that you will get it done by any means necessary, whatever it takes, that the ends justify the means completely. Shooting a porno always feels like a guerilla activity, like you’re contravening some law, morally if not legally. When we were shooting on location in the suburbs of west Berlin, word somehow got out that we were making a porno and we had neighbourhood kids in the trees trying to peer in the windows. It made me realize how hard it must have been for the RAF to try to operate and do all their illegal activities without being ratted out or caught by the police. So I guess you could call us film terrorists.

Tupamaros

The Tupamaros were the band of guerrillas that staged a successful, but short-lived coup in Uruguay in the late sixties. Until the 1990s, with the advent of Peru’s terrorist group “Tupac Amaru,” and the recording star Tupac Amaru Shakur, the Tupamaros were the most prominent people to name themselves after the Inca Chief Tupac Amaru, who fought the Spaniards. Traditionally stationed in the countryside, the Tupamaros took to the cities and temporarily paralyzed Uruguay’s urban capital city Montevideo. News of their success inspired leftists worldwide, who didn’t realize that the small-level success of the Urban Guerrilla concept in a South American country would not necessarily translate into success with the concept in Europe.

Members of the West Berlin’s Kommune I formed a low-level urban guerrilla group called “Tupamaros West Berlin” during the late sixties. Later the group disbanded, and the core members founded the Movement 2 June. Another low-level urban guerrilla group called “Tupamaros Munich” was also formed during the late sixties, but also disbanded without causing much harm.

Urban Guerrilla

“Urban Guerrilla” was the term that the left wing terrorists of German called themselves. The term “Urban Guerrilla” was coined to contrast with the firmly established concept of rural guerrillas whose style of warfare had been utilized for centuries by groups as diverse as the American forces in the Revolutionary War and Chairman Mao’s forces in the 1930s. The difference was that urban guerrillas were to take their wars out of the jungles and mountains, and bring it directly to the population centers.

Carlos Marighella, a South American revolutionary, wrote the definitive field manual for Urban Guerrillas, his Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla. The Baader-Meinhof Gang used Marighella’s book as their bible, though it is clear in retrospect that the book was fatally flawed.

Stammheim

Stammheim was the name of the Stuttgart prison that housed the major Baader-Meinhof defendants during their trials, as well as the courthouse in which they were tried. The section in which the prisoners were kept was billed as the most secure prison block in the world, but this didn’t prevent Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, and their co-defendants from having guns smuggled to them by their lawyers.

The word “Stammheim” took on a greater meaning after the events of “Death Night” in 1977 (when Baader, Ensslin, and Jan-Carl Raspe committed suicide). “Stammheim” came to symbolize the abuse of power by the federal government.

Schili

The Schili were the affluent German leftists who often supported the Baader-Meinhof Gang during their time on the run (they were also called “the Raspberry Reich” or the “Schickeria”). “Schili” was a cross between “chic” (schick), and “left” (linke) and was a somewhat derogatory term. Many of the Schili who supported the outlaw gang members by providing shelter and money, later regretted it when the gang’s activities turned deadly. At the time, however, supporting the Baader-Meinhof Gang was a simple way to live vicariously through their activities.

Springer Press

The bane of leftist Germans, the Springer newspapers were outrageously conservative. Owned by Lord Axel Springer, the Springer Press controlled almost half of the newspaper circulation in West Germany.

Springer was an avowed anti-communist. During a time when others corporations were leaving West Berlin in droves (fearful of the tenuous political situation that barely kept the city out of East German hands), Axel Springer chose to put the headquarters for his publishing empire in Berlin. Springer built a 20-story monstrosity mere yards away from the Berlin Wall (and a block or so away from Checkpoint Charlie), and put a huge reader-board on the side facing East Berlin. The board would flash the news of the free world to the “enslaved Germans” on the other side of the wall. The sheer size of the building was intended as a constant reminder to East Germans of the superiority of the Capitalist system.

The Baader-Meinhof Gang bombed the Springer building in Hamburg in May of 1970, injuring 17 workers.

SPD

Sozialisttischer Parti Demokratic or

Social Democratic Party

The SPD was (and is) the major left-of-center party of Germany, roughly the equivalent of the Democrats in America and Labour in Great Britain (though not necessarily the ideological equivalent).

SDS

Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund or

German Socialist Student Union

Though unconnected to its American counterpart that shared its acronym (Students for a Democratic Society), the German SDS shared a similar place in German society. It was the leading left-wing student organization throughout the sixties (the APO — Extraparliamentary Opposition — was more of a movement than an organization).

Originally the SDS was the student wing of of the SPD party, but the SPD disassociated itself from SDS in 1960 when it began advocating an anti-nuclear bomb stance.

Socialist Patients Collective

Sozialististisches Patienten Kollektiv or

Socialist Patients Collective

The Socialist Patients Collective (SPK) was the strange product of a therapy-group at Heidelberg University. Dr. Wolfgang Huber, a psychiatrist at the university’s clinic, believed that his patients’ mental disorders stemmed from Capitalism, and the only cure was a Marxist society. When the university tried to fire Huber, his patients organized the SPK, held protests, occupied the hospital administration offices, and convinced the university to retain him.

By mid-1971, the SPK had officially disbanded, and many of its former members moved into doing low-level terrorist activities, releasing communiqués after every “praxis,” in keeping with urban guerrilla revolutionary practices. the communiqués stopped being signed with “SPK” and were now being signed “RAF,” though it is not clear that they had any connections to the Red Army Faction at this point. By the time that most of the original members of the RAF were in jail in mid-1970s, many former members of the SPK had joined the RAF.

Revolutionary Cells

Revolutionär Zelles or RZ

The Revolutionary Cells were the third, and least prominent, of the three left-wing terror groups in Germany in the early seventies. Organized into independently functioning cells, the RZ was possibly the most successful of the groups in the sheer number of its terrorist attacks, but they seldom pushed their name to media outlets.

The Revolutionary Cells were formed in Frankfurt am Main around 1972-1973. They specifically rejected the Baader-Meinhof Gang’s approach to group dynamics — that is they felt that having their group go completely underground was self-defeating (it made the Baader-Meinhof group much easier to track down). Instead they organized into semi-autonomous cells, each aware of the group’s overall mission yet mostly unaware of the identities of other group members. Virtually all of the members of Revolutionary Cells were “legals” — meaning they held jobs, had families, and bombed a few buildings on the side. They were said to number in the several hundreds at one point in the mid-1980s, but no one really knows.

One cannot discuss the Revolutionary Cells without talking about another group with the same initials: Rote Zora (RZ). Rote Zora (Red Zora) was originally formed as a sort of women’s auxiliary of the Revolutionary Cells. Later they become more autonomous, and are still occasionally heard from today.

Much was learned about the secretive RZ when a former member, Hans-Joachim Klein (who was in hiding), gave an interview in 1978 to the left-wing Paris magazine Liberation. In the interview he discussed the organizational structure of the RZ. He also mailed his gun to Der Spiegel and sent them a letter denouncing terrorism. The following year Klein published a book (he was still in hiding) about his time in the RZ: “Return to Humanity.”

Red Army Faction

RAF or

Rote Armee Fraktion

The Red Army Faction was the name that the Baader-Meinhof Gang chose for itself. The intent was to portray themselves as faction of a much larger Revolutionary army. Some in the group would later claim that the name was created almost as a joke; modeled after Japan’s “Red Army” terrorists, and also named after the Soviet Union’s “Red Army.” The logo of the Red Army Faction featuring the Hechler and Koch machine pistol.

The RAF almost completely ceased to exist in mid-1972, when the original leaders were jailed, but within the next few years it would be virtually totally revitalized when another group, the SPK, disbanded and remnants of that group joined the RAF. This was the so-called “second generation” RAF; there would be third, and (some would say) fourth and fifth generations as the RAF continued its activities right up into the mid-1990s.

On 20 April 1998, the German BKA announced that an eight-page fax received by the Reuters news agency, claiming that the RAF was disbanding, was authentic. After almost 28 years of terror, and over 30 murders, the RAF was dead.

Praxis

“Practice”

In the study of Marxism in the western world, there was “theory,” which was the discussion of how to best bring about the Revolution, and there was “praxis,” or practice, which was direct action attempting to bring about the revolution. For aspiring terrorists, the primacy of praxis was absolute. It was this allegiance to Marxist theory, and the need for “praxis” to bring about the revolution, that prompted many leftist Germans to support the early actions of the Baader-Meinhof Gang. Later, when bodies began to pile up, the relative mass support for the gang shrank, but their core support hardened.

Lex Baader-Meinhof

Baader-Meinhof Laws

Lex Baader-Meinhof, or the Baader-Meinhof Laws, went into effect on January 1, 1975. They were a series of laws that were designed specifically at the Baader-Meinhof defendants that were on trial in Stammheim. Among the new laws were provisions allowing for trials to continue in the absence of defendants, allowing for lawyers to be barred from trials for almost no reason, and other oppressive measures.

June 2nd Movement

Movement 2 June was the second most prominent left-wing German urban guerrilla group of the seventies. It was founded by former members of Kommune I, and was based in West Berlin.

Movement 2 June was formed in Berlin around 1971. It was built from the remnants of the West Berlin Tupamaros small-level proto-terrorist group which had been around for around three years. The group mostly bombed property targets in Berlin. They named themselves after the date which a young pacifist named Benno Ohnesorg had been killed by police during a 1967 protest in Berlin. They occasionally partnered with the Red Army Faction / Baader-Meinhof Gang with certain actions.

Movement 2 June achieved its greatest “victory” in 1975 when it kidnapped Peter Lorenz, the CDU candidate for Berlin mayor in the upcoming election. The kidnappers demanded and secured the release of four of their imprisoned comrades, who were flown to South Yemen. Lorenz was released unharmed the next day.

Movement 2 June was loosely connected to the Baader-Meinhof Gang, but more often than not, the two groups feuded. Baader-Meinhof was more Marxist in nature, while Movement 2 June was almost anarchist. Movement 2 June disbanded early in the 1980s, with many of its members joining the Red Army Faction (the self-chosen name for the Baader-Meinhof Gang).

konkret

In the late fifties Klaus Rainer Röhl founded a student magazine called the studentkurier, whose name he later changed tokonkret. Röhl later revealed that konkret was almost wholly subsidized in its early years by huge cash infusions from communist East German sources.

As aggressively Marxist as it was aggressively hip, konkret attempted to defy many of the traditional conventions of German publishing, right down to its uncapitalized title. Röhl married Ulrike Meinhof in the early sixties and she quickly became konkret’seditor. After konkret’s East German benefactors pulled their support in the mid-sixties, Röhl changed the format from pure politics to a mix of pornography and politics, and saw the circulation rise exponentially.

Stefan Aust, the greatest of the Baader-Meinhof biographers, followed Meinhof as editor of konkret in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Kalashnikov